Sunday 15 September 1940

Overview: Today is the original target date for Operation Sealion, the invasion of England. The plan in July/August was for the Luftwaffe to take a full month and achieve aerial supremacy over Great Britain, basically driving the RAF from the skies and keeping the Royal Navy out of the English Channel. Then, an invasion would be quite possible, with not only large-scale landings, but effective supply convoys to support the troops and expand the beachheads.

Well, September 15, 1940 now comes and goes with no invasion. History shows that the Luftwaffe came as close as it ever could to achieving aerial supremacy over the British Isles on 6 September, after weeks of focused, effective and hard-fought attacks on the RAF and its infrastructure. On the 7th, however, the Germans radically changed strategy to focus instead on British cities. While that change radically ramped up the miseries of the war for everyone (including, incidentally, Hitler's own people in Berlin and other cities eventually), the Germans making this decision - primarily Adolf Hitler and Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering - thereby sabotaged their own effort. The RAF has recovered and lies in wait, lurking and intact, although cannily not showing all the cards in its hand.

There are many possible psychological layers to this - in fact, it is all psychological analysis in hindsight - and Hitler may in fact already have known by early September that an invasion was not possible. Thus, the change in strategy to bomb cities may not have been as significant as we would like to think - it just flowed from the cold, hard realization that the Luftwaffe already had lost the battle, or at least could never win it. That, incidentally, is the verdict of historians, too, and it is fairly obvious to this one that the Luftwaffe was not "clearing the skies" of the RAF in any kind of timely fashion that would support an invasion.

It is very dangerous to assume that World War II leaders simply made stupid decisions. There usually was a very good reason for them that simply hasn't been explicated by historians for a variety of reasons. World War II leaders such as Hitler were extremely devious and engaged in a lot of misdirection and feints with even their closest subordinates. Though, of course, that doesn't mean that the decisions were always good ones, just that there was an underlying rationale that may not be obvious at hindsight's first glance.

Thus, faced with potentially one of the most important issues of the 20th Century, Hitler temporizes and keeps his own counsel. We can make some guesses, though, on what is really going on. There are many indications from his actions that Hitler is not very serious about the idea of an invasion at any point in September 1940. This includes a very relaxed attitude observed by his closest associates when normally he is extremely nervous before major operations. Hitler always exhibits a decided aversion to major Kriegsmarine operations, even though occasionally he does authorize them anyway with great trepidation (he went through major trauma about Operation Weserubung, for instance, a much less significant event), so his easy-going attitude on the supposed eve of the biggest of them all is a tell on his real thinking. If he was truly serious, Hitler would be in a near-catatonic state of worry.

In addition, Hitler does something else today that shows his mind is elsewhere. He instructs that "No hint of Operation Barbarossa must be given to the Japanese." If Hitler were focusing on Operation Sealion, it is unlikely that he would be giving many thoughts to Operation Barbarossa at this critical juncture. This, incidentally, is a very wise admonition considering later intelligence breaches in Japan. The submission today of the Lossberg Report (see below) further reveals where the real action is in the Fuhrer's mind.

Hitler knows that there are other possible ways to defeat the British - a peripheral strategy in the Mediterranean already advocated by Admiral Reader having a lot more promise than a frontal invasion - and a failed invasion would be a traumatic loss of face for Germany which might even lead to uprisings in territories already conquered. This hugely risky gamble just isn't necessary, especially with his naval counsel - the one who first brought the Operation Sealion idea up and planned the successful Weserubung - telling him it isn't the right time. Finally, Hitler never expected to completely defeat France in 1940 - if at all - so what's the rush?

The view that Hitler is not serious about an invasion is shared by many in the Wehrmacht. They see more of a show being put on by assembling invasion barges (which has the incidental benefit of diverting bombing raids from German cities, which may be part of Hitler's thinking because he often mentions that in similar situations) than any sign that actual troops and tanks are ready to board them. Adolf Galland comments on this directly in his memoirs, noting that never at any point in the battle is there a sense of purpose. If it is just a show, it is a good one, but a show alone is not going to win the war.

Battle of Britain: Today is memorialized as "Battle of Britain Day." The weather is partly cloudy, and the RAF is lying in wait for the Luftwaffe. Hermann Goering has prepared an all-out assault in order to convince Hitler that his Luftwaffe is not the bar to an invasion. The day becomes the basis for "The Battle of Britain" (1969).

The Luftwaffe gets an early start relative to recent weeks, with penetrations around 09:30. Winston Churchill and his wife just happen to be visiting Air Vice-Marshal Keith Park at Uxbridge, and they all go into the operations room together (Churchill seems to have a lifelong sixth sense about major crises: legend has it that he was visiting the New York Stock Exchange on the day of the 1929 crash, too). Upon interception by the RAF, most of the bombers return to base - a most satisfying display by Park for the PM.

An hour later, however, the Luftwaffe sends over a massive formation of KG 2, 26, 53 and 76 bombers and assorted other unis from the Calais/Boulogne region. The Junkers Ju 88s and Dornier Do 17s cross south of Dover, as usual with close escorts of Bf 110s and higher escorts of Bf 109s. It is a massive armada, perhaps the most iconic moment of the entire Battle of Britain.

Park sends up everything that he has at No. 11 Group and also gets help from No. 12 Group. The latter assembles the "Duxford Wing," and this time it has plenty of time to gather its forces together. There is nothing subtle or deceptive about the Luftwaffe formation, this is a brute attack at leisure, as on the 7th of September. Goering really is putting to test the theory that the RAF is finished.

Massive dogfights ensue, and many of the RAF fighters get through to the bombers. As usual, the Spitfires attack the escorts while the Hurricanes focus on the bombers. This is an epic show for those on the ground, seeing aircraft of both sides raining out of the skies.

The bombers generally do not make it to their target of London, and many either drop their bombs at random and flee or get shot down. Their losses become greater as the escorting Bf 109s that remain, low on fuel because of the evasive action taken against the Spitfires, must return to France early. Over London, the RAF administers the coup de grace: the Big Wings of Group No. 12. Douglas Bader's force has a huge opportunity to feast on defenseless and damaged bombers and takes full advantage. Fortunately for the bombers, a stray formation of Bf 109s shows up and disperses the attack, but the RAF fighters still exact great losses.

The bombers do cause a lot of damage, but by and large, it is not to the intended targets. Even those that get through drop their bombs at random over South London, particularly Camberwell, Lambeth, and Lewisham. Whether by luck or design, the London bridges - always difficult targets - receive some bomb strikes. After that, the bombers fly off in a panic in all directions, some heading west, others back east to France. Basically, the bombing raid turns into chaos, with every man out for himself to save his own skin, and there are random bombers everywhere within a huge radius of the city.

At 13:00, the Luftwaffe tries again. This time, the bombers split up rather than a march toward downtown London parade-style again (which, every single time, results in disaster). The RAF response is more ragged because the lesser number of British fighters themselves took casualties and damage and have to be re-armed and refueled. The Luftwaffe has a slight advantage due to its numerical advantage and uses it.

Once again, the RAF intercepts the bombers far from London, but the escorting Bf 109s are in much better shape this time due to the lesser opposition. More bombers make it through to London than in the morning, but once again the "Big Wing" from Duxford is waiting for them. Douglas Bader's fighters had taken much less punishment than the No 11 Group fighters since they had faced primarily bombers rather than fighters during the morning action. However, this time the Big Wing gets a later start and is still getting into formation as the bombers reach the capital. Churchill, at Uxbridge, asks Park what reserves he has left, and Park replies, "None." Of course, there are fighters available in other parts of the country, but in southern England, everything is committed.

London again takes serious damage in its southern and western neighborhoods. The bomber pilots this time are wise to the situation and many, when they see the Bf 109s head for home due to low fuel, simply dump their loads at random and follow. This causes a lot of unintended damage to the eastern neighborhoods of London. Overall, though, the afternoon attack focuses on West Ham, East Ham, Stratford, Stepney, Hackney, Erith, Dartford, and Penge.

There are other attacks during the afternoon, but nothing like the two major morning and early afternoon affairs.

The day is pretty much a disaster for the Luftwaffe. While the RAF loses 36 fighters - no small number - the Luftwaffe loses about 60, with many more badly damaged. Winston Churchill, watching the whole thing with Park at Uxbridge, declares that the:

Goering, in particular, deserves massive blame for the disaster. he exhibits extreme arrogance in sending massive formations across the Channel with absolutely no subtlety, telegraphing the entire thing to the British by preparing his formations over France in full view, and acting as if Fighter Command is irrelevant. The strategy is poor, and the tactics are poorer. It is as if the Luftwaffe has learned nothing from three months of combat over England.

The morning's absolutely insane Luftwaffe parade-ground formation attack does have one silver lining for the Germans, though: it ends once and for all any talk that the RAF is finished. In that sense, it provides invaluable intelligence that the Luftwaffe intelligence arm certainly has provided. The bombers bait Fighter Command into showing what it still has, and that is plenty. It's an expensive way to learn basic things about your enemy, though.

There were numerous classic vignettes during the day, and a couple bears retelling.

Bf 109 pilot Obstlt Dr. Hasso von Wedel, low on fuel, force-lands near Romney Marsh. He plows into a farmhouse shed, killing a mother and daughter waiting to go on a Sunday drive. When a local Constable comes to arrest him, von Wedel apologizes profusely for the incident. The Constable, perplexed, asks him if he would like a spot of tea to calm down.

A Dornier Do 17 of 6,/KG 3 operating toward London gets shot up on the way home, with the pilot incapacitated. He manages to tell the crew over the intercom before fainting, asking that the observer take over the controls. The observer, with only a basic B-2 pilot's license (single-engine), manages to get the plane back across the Channel to a safe landing at Antwerp-Deurne.

There is much over-claiming by the RAF today, with nine separate pilots claiming the Robert Zehbe Dornier that falls on Victoria Station. However, there are enough victories to go around. Several top aces pilots have big days.

RAF pilot James Lacey has a big day. He shoots down a Heinkel He 111 bomber and three Bf 109s.

Douglas Bader gets a victory, a Dornier Do 17 bomber, damages another, and also damages a Junkers Ju 88 over southern England.

Hans-Joachim Marseille downs a Hurricane over south-east London for his fourth victory.

European Air Operations: Bomber Command focuses on the invasion ports.

During an attack on the barges at Antwerp, 18-year-old radio operator/gunner Sergeant John Hannah fights a fire in a Hampden bomber. His actions allow the pilot to return to base. Hannah receives the Victoria Cross. The citation notes that not only did Hannah put out the fire, receiving burns to his face and eyes, but he also retrieves the log and maps of the navigator (who had parachuted out) for the pilot.

Battle of the Atlantic: After several days of little activity, the U-boat fleet strikes again. A wolfpack has gathered around Convoy SC 3 west of the Hebrides. Kapitänleutnant Heinrich Bleichrodt in U-48 gets several victories, while Kapitänleutnant Otto Kretschmer in U-99 also gets a victory during a wild coordinated attack on the convoy. Kretschmer is not only one of the most successful U-boat commanders, he also is without question the most imaginative and daring commander who creates opportunities for others.

Kretschmer starts things off. A few minutes past midnight, U-99 surfaces and shells 1780 ton Canadian freighter Kenordoc in Convoy SC 3. The ship survives long enough for escorts to take off 13 survivors. The escorts later scuttle the burning ship. There are 7 deaths.

Taking advantage of the confusion, U-48 then torpedoes and sinks one of the escorts of Convoy SC 3, 1,060-ton sloop HMS Dundee at 00:25. There are 83 survivors and 12 deaths.

About an hour later, U-48 strikes again. At 01:23, it torpedoes and sinks 4343 ton Greek freighter Alexandros. The Alexandros normally would sink right away, but its freight is timber, which keeps it afloat for a while and enables one of the escorts to grab the survivors in the dark. There are 23 survivors, with 5 deaths.

U-48 waits until 03:00, then strikes again. It torpedoes and sinks 5319-ton British freighter Empire Volunteer. There are 33 survivors and six crew perish.

U-48 also attacks the British freighter Empire Soldier but misses.

Another convoy not far away (about 90 miles from Rockall, Convoy HX 70, also is attacked late in the day. U-65 (Kapitänleutnant Hans-Gerrit von Stockhausen), on its fourth patrol and operating out of Lorient, torpedoes and sinks 4950-ton Norwegian freighter Hird at 22:30. Everybody survives, rescued by Icelandic trawler Icelandic Þórólfur (English: Thorolf). The attack is difficult, with the first torpedo around an hour earlier missing but seen by the freighter's crew. The Hird thus begins zig-zagging at full speed. Stockhausen, however, exercises extreme patience, and the zig-zagging allows him to keep up with the freighter.

The Luftwaffe also gets a couple of victories, and the day is a good example of the multi-faceted blockade the Germans are imposing on Great Britain.

The Luftwaffe bombs 5548-ton British wheat freighter Nailsea River about 4 miles off Montrose, Angus in the North Sea. The Nailsea River is in Convoy SL 45, and everybody aboard is rescued.

The Luftwaffe bombs and sinks 1264 ton British freighter Halland about 15 km east of Dunbar, East Lothian in the North Sea. This time, everybody aboard, 17 men, perishes. The merchant marine really is a lottery, with entire crews living or dying based solely on the circumstances of how and where they are attacked.

The Luftwaffe also damages British freighter Stanwold at Southampton and Dutch freighter Veerhaven at the London docks.

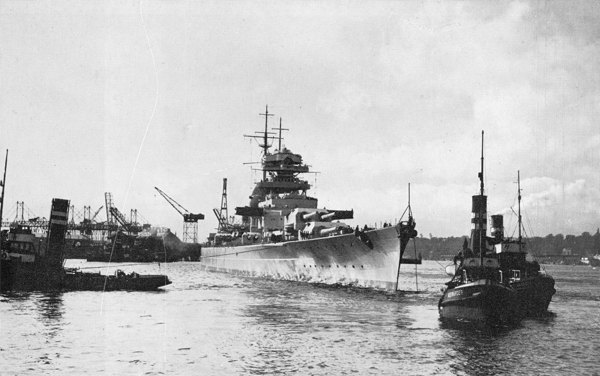

The Bismarck departs from its home anchorage for the first time and moves down the Kiel Canal. She is being put into a position to assist with Operation Sealion should Hitler approve the invasion. En route, the battleship collides with the bow tug "Atlantik" but shrugs it off. During the night, while anchored at Brunsbüttel roads, she gets more anti-aircraft practice but does not score any hits on the attacking British bombers.

German torpedo boats lay minefield Bernhard in the Dover Strait in preparation for Operation Sealion.

Convoy MS, part of Operation Menace, arrives at Freetown.

Convoy FN 281 departs from Southend, Convoy MT 170 departs from Methil, Convoy FS 282 departs from the Tyne, Convoy OB 214 departs from Liverpool,

Battle of the Mediterranean: The Italians advancing down Halfaya Pass link up with the troops advancing along the coast. The British, reinforced with a company of Free French marines and the 11th Hussars, retreat to Alam Hamid. The British destroy the coast road as they retreat, causing the Italians problems since that is their sole route of advance.

The British Long Range Patrol Unit (the "Desert Rats") operate far out in the desert to the south of the Italian invasion. "W" patrol ascertains that the Italian effort is solely along the coast road and engage in harassing activities such as blowing up Italian supplies and capturing an Italian convoy to Kufra. "T" Patrol performs reconnaissance in the direction of Uweinat in eastern Libya.

British submarine Pandora unsuccessfully attacks an Italian freighter off Benghazi, Libya.

At Malta, Bf 109 fighters are spotted for the first time. Six of them escort (along with 10 CR 42 biplanes) a formation of 20 Junkers Ju 87 Stukas on a 08:00 air raid. The Stukas bomb Hal Far airfield, injuring nine people. There are 17 unexploded bombs at the airfield which turn out to have delayed-action fuzes. Fortunately for the British, they are in an unnecessary portion of the field. This is a major expansion of the German presence in the Mediterranean.

Anglo/US Relations: Five formerly US destroyers depart from St. John, New Brunswick, headed for Belfast.

German/Spanish Relations: Hitler requests that the Spanish grant the Germans bases in the Canary Islands and its other possessions. Franco does not respond immediately.

Canadian Military: Conscription is imposed on single men aged 21-24.

The British Ministry of Supply submits a request for Canada to build a factory to produce phosgene gas. Phosgene was the most deadly poison gas used in World War I, accounting for 85% of the 100,000 poison-gas deaths in that conflict. Poison gas is outlawed by international law, specifically the 1925 Geneva Protocol, and its use would be a war crime.

German Military: Lieutenant Colonel Bernhard von Lossberg submits a report that becomes known as the Lossberg study to Colonel General Alfred Jodl at OKW. A plan for Operation Barbarossa, it gives priority to the northward axis of attack in the Soviet Union. This is due to good communications, important objectives and Finnish cooperation. Hitler approves the northward orientation, which is maintained throughout the planning process and the ultimate invasion.

Soviet Military: Military conscription is imposed on 19- and 20-year-olds.

Japanese Military: Japanese carrier Soryu transfers its air units to carrier Hiryu while it undergoes a refit.

Sweden: The Swedish Social Democratic Party receives over half the votes in national elections.

China: Chungking is bombed again by Japanese Nakajima B5N "Kate" bombers of the 12th Naval Air Group based in Yichang, Hubei Province.

At the continuing Battle of South Kwangsi, Chinese forces attack the lines of communication for the Japanese 22nd Army around Nanning and Lungchin. The Japanese have withdrawn the elite 5th Infantry Division from the area to spearhead the projected invasion of French Indochina, planned to begin in a week's time.

Future History: Lynn Jay and Merle Barrus Olsen is born in Logan, Utah. Better known as Merlin Olsen, he becomes a Hall of Fame defensive lineman for the Los Angeles Rams in the 1960s, and later an NBC broadcaster and actor. He passes away in 2010.

September 1940

September 1, 1940: RAF's Horrible Weekend

September 2, 1940: German Troopship Sunk

September 3, 1940: Destroyers for Bases

September 4, 1940: Enter Antonescu

September 5, 1940: Stukas Over Malta

September 6, 1940: The Luftwaffe Peaks

September 7, 1940: The Blitz Begins

September 8, 1940: Codeword Cromwell

September 9, 1940: Italians Attack Egypt

September 10, 1940: Hitler Postpones Sealion

September 11, 1940: British Confusion at Gibraltar

September 12, 1940: Warsaw Ghetto Approved

September 13, 1940: Zeros Attack!

September 14, 1940: The Draft Is Back

September 15, 1940: Battle of Britain Day

September 16, 1940: italians Take Sidi Barrani

September 17, 1940: Sealion Kaputt

September 18, 1940: City of Benares Incident

September 19, 1940: Disperse the Barges

September 20, 1940: A Wolfpack Gathers

September 21, 1940: Wolfpack Strikes Convoy HX-72

September 22, 1940: Vietnam War Begins

September 23, 1940: Operation Menace Begins

September 24, 1940: Dakar Fights Back

September 25, 1940: Filton Raid

September 26, 1940: Axis Time

September 27, 1940: Graveney Marsh Battle

September 28, 1940: Radio Belgique Begins

September 29, 1940: Brocklesby Collision

September 30, 1940: Operation Lena

2020

Well, September 15, 1940 now comes and goes with no invasion. History shows that the Luftwaffe came as close as it ever could to achieving aerial supremacy over the British Isles on 6 September, after weeks of focused, effective and hard-fought attacks on the RAF and its infrastructure. On the 7th, however, the Germans radically changed strategy to focus instead on British cities. While that change radically ramped up the miseries of the war for everyone (including, incidentally, Hitler's own people in Berlin and other cities eventually), the Germans making this decision - primarily Adolf Hitler and Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering - thereby sabotaged their own effort. The RAF has recovered and lies in wait, lurking and intact, although cannily not showing all the cards in its hand.

There are many possible psychological layers to this - in fact, it is all psychological analysis in hindsight - and Hitler may in fact already have known by early September that an invasion was not possible. Thus, the change in strategy to bomb cities may not have been as significant as we would like to think - it just flowed from the cold, hard realization that the Luftwaffe already had lost the battle, or at least could never win it. That, incidentally, is the verdict of historians, too, and it is fairly obvious to this one that the Luftwaffe was not "clearing the skies" of the RAF in any kind of timely fashion that would support an invasion.

It is very dangerous to assume that World War II leaders simply made stupid decisions. There usually was a very good reason for them that simply hasn't been explicated by historians for a variety of reasons. World War II leaders such as Hitler were extremely devious and engaged in a lot of misdirection and feints with even their closest subordinates. Though, of course, that doesn't mean that the decisions were always good ones, just that there was an underlying rationale that may not be obvious at hindsight's first glance.

Thus, faced with potentially one of the most important issues of the 20th Century, Hitler temporizes and keeps his own counsel. We can make some guesses, though, on what is really going on. There are many indications from his actions that Hitler is not very serious about the idea of an invasion at any point in September 1940. This includes a very relaxed attitude observed by his closest associates when normally he is extremely nervous before major operations. Hitler always exhibits a decided aversion to major Kriegsmarine operations, even though occasionally he does authorize them anyway with great trepidation (he went through major trauma about Operation Weserubung, for instance, a much less significant event), so his easy-going attitude on the supposed eve of the biggest of them all is a tell on his real thinking. If he was truly serious, Hitler would be in a near-catatonic state of worry.

In addition, Hitler does something else today that shows his mind is elsewhere. He instructs that "No hint of Operation Barbarossa must be given to the Japanese." If Hitler were focusing on Operation Sealion, it is unlikely that he would be giving many thoughts to Operation Barbarossa at this critical juncture. This, incidentally, is a very wise admonition considering later intelligence breaches in Japan. The submission today of the Lossberg Report (see below) further reveals where the real action is in the Fuhrer's mind.

Hitler knows that there are other possible ways to defeat the British - a peripheral strategy in the Mediterranean already advocated by Admiral Reader having a lot more promise than a frontal invasion - and a failed invasion would be a traumatic loss of face for Germany which might even lead to uprisings in territories already conquered. This hugely risky gamble just isn't necessary, especially with his naval counsel - the one who first brought the Operation Sealion idea up and planned the successful Weserubung - telling him it isn't the right time. Finally, Hitler never expected to completely defeat France in 1940 - if at all - so what's the rush?

The view that Hitler is not serious about an invasion is shared by many in the Wehrmacht. They see more of a show being put on by assembling invasion barges (which has the incidental benefit of diverting bombing raids from German cities, which may be part of Hitler's thinking because he often mentions that in similar situations) than any sign that actual troops and tanks are ready to board them. Adolf Galland comments on this directly in his memoirs, noting that never at any point in the battle is there a sense of purpose. If it is just a show, it is a good one, but a show alone is not going to win the war.

|

| A civil defense worker inspects the wing (notice the bullet holes) of the Dornier Do 17 on Victoria Station, 15 September 1940. |

The Luftwaffe gets an early start relative to recent weeks, with penetrations around 09:30. Winston Churchill and his wife just happen to be visiting Air Vice-Marshal Keith Park at Uxbridge, and they all go into the operations room together (Churchill seems to have a lifelong sixth sense about major crises: legend has it that he was visiting the New York Stock Exchange on the day of the 1929 crash, too). Upon interception by the RAF, most of the bombers return to base - a most satisfying display by Park for the PM.

An hour later, however, the Luftwaffe sends over a massive formation of KG 2, 26, 53 and 76 bombers and assorted other unis from the Calais/Boulogne region. The Junkers Ju 88s and Dornier Do 17s cross south of Dover, as usual with close escorts of Bf 110s and higher escorts of Bf 109s. It is a massive armada, perhaps the most iconic moment of the entire Battle of Britain.

Park sends up everything that he has at No. 11 Group and also gets help from No. 12 Group. The latter assembles the "Duxford Wing," and this time it has plenty of time to gather its forces together. There is nothing subtle or deceptive about the Luftwaffe formation, this is a brute attack at leisure, as on the 7th of September. Goering really is putting to test the theory that the RAF is finished.

Massive dogfights ensue, and many of the RAF fighters get through to the bombers. As usual, the Spitfires attack the escorts while the Hurricanes focus on the bombers. This is an epic show for those on the ground, seeing aircraft of both sides raining out of the skies.

The bombers generally do not make it to their target of London, and many either drop their bombs at random and flee or get shot down. Their losses become greater as the escorting Bf 109s that remain, low on fuel because of the evasive action taken against the Spitfires, must return to France early. Over London, the RAF administers the coup de grace: the Big Wings of Group No. 12. Douglas Bader's force has a huge opportunity to feast on defenseless and damaged bombers and takes full advantage. Fortunately for the bombers, a stray formation of Bf 109s shows up and disperses the attack, but the RAF fighters still exact great losses.

|

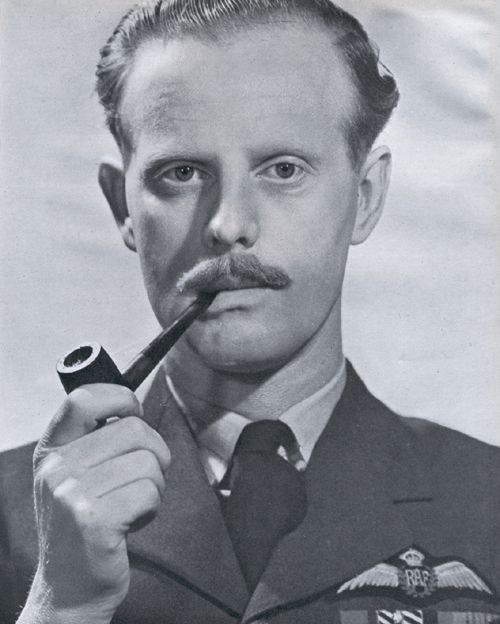

| Sgt Dennis H "Nick" Nichols joins No 56 Squadron at RAF Boscombe Down on 15 September 1940, aged 19. Quite a day to commence one's career. |

At 13:00, the Luftwaffe tries again. This time, the bombers split up rather than a march toward downtown London parade-style again (which, every single time, results in disaster). The RAF response is more ragged because the lesser number of British fighters themselves took casualties and damage and have to be re-armed and refueled. The Luftwaffe has a slight advantage due to its numerical advantage and uses it.

Once again, the RAF intercepts the bombers far from London, but the escorting Bf 109s are in much better shape this time due to the lesser opposition. More bombers make it through to London than in the morning, but once again the "Big Wing" from Duxford is waiting for them. Douglas Bader's fighters had taken much less punishment than the No 11 Group fighters since they had faced primarily bombers rather than fighters during the morning action. However, this time the Big Wing gets a later start and is still getting into formation as the bombers reach the capital. Churchill, at Uxbridge, asks Park what reserves he has left, and Park replies, "None." Of course, there are fighters available in other parts of the country, but in southern England, everything is committed.

London again takes serious damage in its southern and western neighborhoods. The bomber pilots this time are wise to the situation and many, when they see the Bf 109s head for home due to low fuel, simply dump their loads at random and follow. This causes a lot of unintended damage to the eastern neighborhoods of London. Overall, though, the afternoon attack focuses on West Ham, East Ham, Stratford, Stepney, Hackney, Erith, Dartford, and Penge.

There are other attacks during the afternoon, but nothing like the two major morning and early afternoon affairs.

The day is pretty much a disaster for the Luftwaffe. While the RAF loses 36 fighters - no small number - the Luftwaffe loses about 60, with many more badly damaged. Winston Churchill, watching the whole thing with Park at Uxbridge, declares that the:

fifteenth of September 1940 was the day of our Victory!Much has been written about the Battle of Britain Day, and, as noted above, they have made an entire legendary film about it (though with great creative license). It is the climax of the Battle of Britain and the ultimate failure of the Hitler/Goering strategy of targeting London.

Goering, in particular, deserves massive blame for the disaster. he exhibits extreme arrogance in sending massive formations across the Channel with absolutely no subtlety, telegraphing the entire thing to the British by preparing his formations over France in full view, and acting as if Fighter Command is irrelevant. The strategy is poor, and the tactics are poorer. It is as if the Luftwaffe has learned nothing from three months of combat over England.

The morning's absolutely insane Luftwaffe parade-ground formation attack does have one silver lining for the Germans, though: it ends once and for all any talk that the RAF is finished. In that sense, it provides invaluable intelligence that the Luftwaffe intelligence arm certainly has provided. The bombers bait Fighter Command into showing what it still has, and that is plenty. It's an expensive way to learn basic things about your enemy, though.

There were numerous classic vignettes during the day, and a couple bears retelling.

Bf 109 pilot Obstlt Dr. Hasso von Wedel, low on fuel, force-lands near Romney Marsh. He plows into a farmhouse shed, killing a mother and daughter waiting to go on a Sunday drive. When a local Constable comes to arrest him, von Wedel apologizes profusely for the incident. The Constable, perplexed, asks him if he would like a spot of tea to calm down.

A Dornier Do 17 of 6,/KG 3 operating toward London gets shot up on the way home, with the pilot incapacitated. He manages to tell the crew over the intercom before fainting, asking that the observer take over the controls. The observer, with only a basic B-2 pilot's license (single-engine), manages to get the plane back across the Channel to a safe landing at Antwerp-Deurne.

There is much over-claiming by the RAF today, with nine separate pilots claiming the Robert Zehbe Dornier that falls on Victoria Station. However, there are enough victories to go around. Several top aces pilots have big days.

RAF pilot James Lacey has a big day. He shoots down a Heinkel He 111 bomber and three Bf 109s.

Douglas Bader gets a victory, a Dornier Do 17 bomber, damages another, and also damages a Junkers Ju 88 over southern England.

Hans-Joachim Marseille downs a Hurricane over south-east London for his fourth victory.

|

| As usual, the London papers are full of sensational claims. However, today they are not as far off as usual. |

During an attack on the barges at Antwerp, 18-year-old radio operator/gunner Sergeant John Hannah fights a fire in a Hampden bomber. His actions allow the pilot to return to base. Hannah receives the Victoria Cross. The citation notes that not only did Hannah put out the fire, receiving burns to his face and eyes, but he also retrieves the log and maps of the navigator (who had parachuted out) for the pilot.

Kretschmer starts things off. A few minutes past midnight, U-99 surfaces and shells 1780 ton Canadian freighter Kenordoc in Convoy SC 3. The ship survives long enough for escorts to take off 13 survivors. The escorts later scuttle the burning ship. There are 7 deaths.

Taking advantage of the confusion, U-48 then torpedoes and sinks one of the escorts of Convoy SC 3, 1,060-ton sloop HMS Dundee at 00:25. There are 83 survivors and 12 deaths.

About an hour later, U-48 strikes again. At 01:23, it torpedoes and sinks 4343 ton Greek freighter Alexandros. The Alexandros normally would sink right away, but its freight is timber, which keeps it afloat for a while and enables one of the escorts to grab the survivors in the dark. There are 23 survivors, with 5 deaths.

U-48 waits until 03:00, then strikes again. It torpedoes and sinks 5319-ton British freighter Empire Volunteer. There are 33 survivors and six crew perish.

U-48 also attacks the British freighter Empire Soldier but misses.

Another convoy not far away (about 90 miles from Rockall, Convoy HX 70, also is attacked late in the day. U-65 (Kapitänleutnant Hans-Gerrit von Stockhausen), on its fourth patrol and operating out of Lorient, torpedoes and sinks 4950-ton Norwegian freighter Hird at 22:30. Everybody survives, rescued by Icelandic trawler Icelandic Þórólfur (English: Thorolf). The attack is difficult, with the first torpedo around an hour earlier missing but seen by the freighter's crew. The Hird thus begins zig-zagging at full speed. Stockhausen, however, exercises extreme patience, and the zig-zagging allows him to keep up with the freighter.

The Luftwaffe also gets a couple of victories, and the day is a good example of the multi-faceted blockade the Germans are imposing on Great Britain.

The Luftwaffe bombs 5548-ton British wheat freighter Nailsea River about 4 miles off Montrose, Angus in the North Sea. The Nailsea River is in Convoy SL 45, and everybody aboard is rescued.

The Luftwaffe bombs and sinks 1264 ton British freighter Halland about 15 km east of Dunbar, East Lothian in the North Sea. This time, everybody aboard, 17 men, perishes. The merchant marine really is a lottery, with entire crews living or dying based solely on the circumstances of how and where they are attacked.

The Luftwaffe also damages British freighter Stanwold at Southampton and Dutch freighter Veerhaven at the London docks.

The Bismarck departs from its home anchorage for the first time and moves down the Kiel Canal. She is being put into a position to assist with Operation Sealion should Hitler approve the invasion. En route, the battleship collides with the bow tug "Atlantik" but shrugs it off. During the night, while anchored at Brunsbüttel roads, she gets more anti-aircraft practice but does not score any hits on the attacking British bombers.

German torpedo boats lay minefield Bernhard in the Dover Strait in preparation for Operation Sealion.

Convoy MS, part of Operation Menace, arrives at Freetown.

Convoy FN 281 departs from Southend, Convoy MT 170 departs from Methil, Convoy FS 282 departs from the Tyne, Convoy OB 214 departs from Liverpool,

|

| The Bismarck moves down the Kiel Canal, 15 September 1940. |

The British Long Range Patrol Unit (the "Desert Rats") operate far out in the desert to the south of the Italian invasion. "W" patrol ascertains that the Italian effort is solely along the coast road and engage in harassing activities such as blowing up Italian supplies and capturing an Italian convoy to Kufra. "T" Patrol performs reconnaissance in the direction of Uweinat in eastern Libya.

British submarine Pandora unsuccessfully attacks an Italian freighter off Benghazi, Libya.

At Malta, Bf 109 fighters are spotted for the first time. Six of them escort (along with 10 CR 42 biplanes) a formation of 20 Junkers Ju 87 Stukas on a 08:00 air raid. The Stukas bomb Hal Far airfield, injuring nine people. There are 17 unexploded bombs at the airfield which turn out to have delayed-action fuzes. Fortunately for the British, they are in an unnecessary portion of the field. This is a major expansion of the German presence in the Mediterranean.

German/Spanish Relations: Hitler requests that the Spanish grant the Germans bases in the Canary Islands and its other possessions. Franco does not respond immediately.

Canadian Military: Conscription is imposed on single men aged 21-24.

The British Ministry of Supply submits a request for Canada to build a factory to produce phosgene gas. Phosgene was the most deadly poison gas used in World War I, accounting for 85% of the 100,000 poison-gas deaths in that conflict. Poison gas is outlawed by international law, specifically the 1925 Geneva Protocol, and its use would be a war crime.

German Military: Lieutenant Colonel Bernhard von Lossberg submits a report that becomes known as the Lossberg study to Colonel General Alfred Jodl at OKW. A plan for Operation Barbarossa, it gives priority to the northward axis of attack in the Soviet Union. This is due to good communications, important objectives and Finnish cooperation. Hitler approves the northward orientation, which is maintained throughout the planning process and the ultimate invasion.

Soviet Military: Military conscription is imposed on 19- and 20-year-olds.

|

| Japanese submarine I-15, 15 September 1940. |

Sweden: The Swedish Social Democratic Party receives over half the votes in national elections.

China: Chungking is bombed again by Japanese Nakajima B5N "Kate" bombers of the 12th Naval Air Group based in Yichang, Hubei Province.

At the continuing Battle of South Kwangsi, Chinese forces attack the lines of communication for the Japanese 22nd Army around Nanning and Lungchin. The Japanese have withdrawn the elite 5th Infantry Division from the area to spearhead the projected invasion of French Indochina, planned to begin in a week's time.

Future History: Lynn Jay and Merle Barrus Olsen is born in Logan, Utah. Better known as Merlin Olsen, he becomes a Hall of Fame defensive lineman for the Los Angeles Rams in the 1960s, and later an NBC broadcaster and actor. He passes away in 2010.

|

| One of only two (partial) Nakajima B5N "Kate" bombers known to survive, on display at the Pacific Aviation Museum at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. It is undergoing a complete restoration. |

September 1, 1940: RAF's Horrible Weekend

September 2, 1940: German Troopship Sunk

September 3, 1940: Destroyers for Bases

September 4, 1940: Enter Antonescu

September 5, 1940: Stukas Over Malta

September 6, 1940: The Luftwaffe Peaks

September 7, 1940: The Blitz Begins

September 8, 1940: Codeword Cromwell

September 9, 1940: Italians Attack Egypt

September 10, 1940: Hitler Postpones Sealion

September 11, 1940: British Confusion at Gibraltar

September 12, 1940: Warsaw Ghetto Approved

September 13, 1940: Zeros Attack!

September 14, 1940: The Draft Is Back

September 15, 1940: Battle of Britain Day

September 16, 1940: italians Take Sidi Barrani

September 17, 1940: Sealion Kaputt

September 18, 1940: City of Benares Incident

September 19, 1940: Disperse the Barges

September 20, 1940: A Wolfpack Gathers

September 21, 1940: Wolfpack Strikes Convoy HX-72

September 22, 1940: Vietnam War Begins

September 23, 1940: Operation Menace Begins

September 24, 1940: Dakar Fights Back

September 25, 1940: Filton Raid

September 26, 1940: Axis Time

September 27, 1940: Graveney Marsh Battle

September 28, 1940: Radio Belgique Begins

September 29, 1940: Brocklesby Collision

September 30, 1940: Operation Lena

2020

No comments:

Post a Comment