Sunday 18 August 1940

|

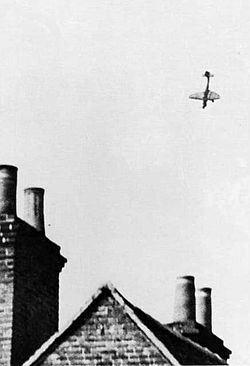

| Dornier Do 17 bombers coming in at wavetop level to avoid radar detection. This is the group that gets wiped out at RAF Kenley by arriving there first. |

Battle of Britain: After a day of rest, the air battle returns full-bore today, 18 August 1940. The outcome, though, follows the norm of the past month: the RAF loses far fewer planes than the Luftwaffe but has its substance slowly eroded as the Germans pound its airfields, radar stations and factories. This is known as "The Hardest Day" due to the fact that more aircraft are lost today than on any other day of the Battle of Britain.

The day begins poorly for the Luftwaffe when it loses a Junkers Ju 88 during the night and then a reconnaissance Bf 110 of LG 2 over RAF Manston. The latter presages that the main effort of the day is aimed at RAF airfields, which took a huge beating on 15 August.

KG 26 and KG 76 attack RAF Kenley first at around noon - three hours behind schedule due to fears about the weather. It is a highly coordinated attack, with a lot of moving parts. Twenty Bf 109s of JG 51 serve as escorts. Wave after wave of different groups of bombers - first Junkers Ju 88s, then Dornier Do 17s, then another group of Dorniers flying in at tree-top level. The plan is to string out the defense and overwhelm it. Everything is planned out precisely, with different waves of bombers planned to come in at five or ten-minute intervals. On paper, it is an ideal plan.

Another attack at around the same time is made on RAF Biggin Hill by KG 1, escorted by JG 54. In addition, it is planned that a "Freie Jagd" (target of opportunity patrol) by the elite JG 26 and JG 3 would also be in the area.

Things start going wrong due to heavy cloud cover. The bombers and the escorts have difficulty finding each other, and also the winds are against certain formations. The result is that the bombing attacks turn into a mish-mash of Luftwaffe bombers appearing over the targets at random. In fact, a group of Dorniers without escort reach the target first.

RAF No. 111 Squadron gets over Kenley airfield early, and the British anti-aircraft guns are ready for action, with plenty of radar warning due to the swarms of Luftwaffe planes approaching from all directions. In addition, the RAF uses the "cable bombs," which are cables shot into the air and which hang in the air from parachutes over the targets. It is not a very effective weapon, but it does snag a bomber or two.

The result is the wholesale slaughter of the first batch of Dornier bombers over Kenley. They were supposed to be the last to arrive after the defenses already have been disrupted and came the whole way at wavetop/treetop level to avoid detection. Instead, the defenses are fresh and waiting for them. Those bombers that don't get shot down or snagged by cables are badly damaged and either crash in the Channel or make it back to France as total wrecks. Only one bomber from this formation makes it home. Kenley, however, is badly damaged, including the hospital there, and is only partially operational after the attack. Biggin Hill, though, escapes without too much damage. The other airfields are soon operational.

The rest of the day is a sequence of chaotic, confusing actions over various RAF airfields. RAF Gosport, Ford, and Thorney Island receive attention, the radar station at Poling is attacked at 14:00, Portsmouth is hit, and RAF Manston gets strafed. Basically, the entire coordinated attack breaks down, and it is "every formation for itself." One Bf 110 pilot only survives after being badly damaged by spiraling in trailing smoke to appear like a write-off, then pulling out at the last second and scooting for France. It is that kind of day, men fighting desperately for their lives and pulling out all their tricks just to stay alive.

The day begins poorly for the Luftwaffe when it loses a Junkers Ju 88 during the night and then a reconnaissance Bf 110 of LG 2 over RAF Manston. The latter presages that the main effort of the day is aimed at RAF airfields, which took a huge beating on 15 August.

KG 26 and KG 76 attack RAF Kenley first at around noon - three hours behind schedule due to fears about the weather. It is a highly coordinated attack, with a lot of moving parts. Twenty Bf 109s of JG 51 serve as escorts. Wave after wave of different groups of bombers - first Junkers Ju 88s, then Dornier Do 17s, then another group of Dorniers flying in at tree-top level. The plan is to string out the defense and overwhelm it. Everything is planned out precisely, with different waves of bombers planned to come in at five or ten-minute intervals. On paper, it is an ideal plan.

Another attack at around the same time is made on RAF Biggin Hill by KG 1, escorted by JG 54. In addition, it is planned that a "Freie Jagd" (target of opportunity patrol) by the elite JG 26 and JG 3 would also be in the area.

Things start going wrong due to heavy cloud cover. The bombers and the escorts have difficulty finding each other, and also the winds are against certain formations. The result is that the bombing attacks turn into a mish-mash of Luftwaffe bombers appearing over the targets at random. In fact, a group of Dorniers without escort reach the target first.

RAF No. 111 Squadron gets over Kenley airfield early, and the British anti-aircraft guns are ready for action, with plenty of radar warning due to the swarms of Luftwaffe planes approaching from all directions. In addition, the RAF uses the "cable bombs," which are cables shot into the air and which hang in the air from parachutes over the targets. It is not a very effective weapon, but it does snag a bomber or two.

The result is the wholesale slaughter of the first batch of Dornier bombers over Kenley. They were supposed to be the last to arrive after the defenses already have been disrupted and came the whole way at wavetop/treetop level to avoid detection. Instead, the defenses are fresh and waiting for them. Those bombers that don't get shot down or snagged by cables are badly damaged and either crash in the Channel or make it back to France as total wrecks. Only one bomber from this formation makes it home. Kenley, however, is badly damaged, including the hospital there, and is only partially operational after the attack. Biggin Hill, though, escapes without too much damage. The other airfields are soon operational.

|

| Junkers Ju 87 Stuka on the way down. Unteroffizer August Dann and Unteroffizer Erich Kohl perish. |

The Luftwaffe loses 17 Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers during the day (out of 109 committed to action). Ten are lost just in the Thorney Island raid. It is the single worst day for the Stuka force during the war, at least to this point. Six others are badly damaged for an overall attrition rate of over 20%. After this, the Stukas basically are withdrawn from the battle, though they remain available at the Pas de Calais for targeted strikes, particularly against naval targets and to support Operation Sea Lion (the invasion of Great Britain that never takes place). Looking ahead, the Stukas are withdrawn completely only when Sea Lion is finally canceled in September 1940.

The Luftwaffe damages British dredge ship Lyster at Liverpool.

Sgt. Bruce Hancock, an RAF pilot, uses his unarmed training plane to ram a Luftwaffe bomber and perishes.

The day's losses are usually touted as 60-75 losses for the Luftwaffe and 30-40 for the RAF. This, however, does not count numerous aircraft (one estimate is 29, including half a dozen fighters) destroyed on RAF airfields, so things are not quite as bad for the Luftwaffe as it might appear based on the aerial combat losses. One can with confidence say that air losses for the day were heavy for both sides and favored the RAF by roughly 2-1, while planes actually destroyed were about even.

However, the numbers also understate the problems caused for the Luftwaffe. The numbers do not come close to reflecting the chaos and the damage suffered. GruppenKommandeur Hptm. Herbert Meisel of I,/StG 77 is killed, Lt. Walter Blume of 7./JG 26 (14 victories) becomes a POW, Oblt. Helmut Teidmann of 2./JG 3 (7 victories) becomes a POW, Staffelkapitän of 5./JG 51 Hptm. Horst Tietzen is killed - the list of very talented and successful pilots lost is long. When that many top pilots are lost, something is going seriously wrong. Fortunately for Adolf Galland, he is at Carinhall receiving a decoration and misses the "fun," but the losses are absolutely crippling for several formations.

The RAF also loses a dozen pilots, and that is not trivial. Most of their men, however, can parachute to safety and be back with their Squadrons by suppertime. The Germans shot down over England are gone for good, and there are scads of them. It is fair to say that neither side really knows how the other is holding up, so the day puts everyone on edge.

The RAF also makes some attacks of its own. RAF Coastal Command attacks Boulogne, and Bomber Command raids the Italian aircraft works at Milan and Turin again. Other attacks are made against Luftwaffe airfields at Freiburg and Habsheim, and industrial targets at Waldshut and Bad Rheinfelden are bombed.

Due to heavy losses, JG 52 is pulled from the Channel and transferred back to Jever to fly defensive missions against RAF Bomber Command. In addition, Ju 87 Stukas finally are withdrawn from attacks inland.

German Government: The summer is wearing on, and Operation Sea Lion is no nearer to having its preconditions fulfilled. It is not, however, the Luftwaffe's fault, for it is fighting its heart out with inadequate equipment and delusional commanders. The problem is the Kriegsmarine. It continues to reveal just how unprepared it is for a cross-Channel expedition of any kind, which is a bit of a farce because the navy was the service pushing the idea of an invasion hardest in the first place. While Wilhelm Keitel can issue fatuous orders about "compromise" between the army and navy conceptions of an invasion, reality intrudes. The army can insist all it wants on inserting an entire army group on the English shores at once, but everything ultimately boils down to the Kriegsmarine and what it can actually do. There is only one conclusion to be drawn as the high command reviews the facts: the Kriegsmarine simply does not have the ships pretty much regardless of what the Luftwaffe does from now on.

There is scapegoating everywhere in the German high command. Hermann Goering blames "local commanders," Admiral Raeder blames the Luftwaffe, the Army blames the Kriegsmarine, and Hitler apparently doesn't even really want to invade anyway. One thing is for certain, things have to improve fast or the entire military strategy against Great Britain is bankrupt.

Battle of the Atlantic: U-48 (K.Kapt. Hans-Rudolf Rösing) torpedoes and sinks 7,590-ton Belgian freighter Ville de Gand (some sources place the sinking on the 19th).

Armed merchant cruiser Circassia eludes an attack by an unknown U-boat, then counterattacks without success (but claims it sank the U-boat). Nobody has been able to identify the U-boat.

Cruiser HMS Delhi stops Spanish freighter Ciudad de Seville and Portuguese freighter Joao Belo. It sends the former to Freetown and interns six Germans on the latter.

Convoys OA 201 and MT 144 depart from Methil, Convoy FN 256 departs from Southend, Convoy FS 256 departs the Tyne, Convoy OB 200 departs from Liverpool, Convoy SL 44 departs from Freetown, BS 3 departs from Suez.

Battle of the Mediterranean: At Malta, there are no raids. Three Blenheim bombers fly in for operations.

British Somaliland: The Black Watch rear guard boards the transports at Berbera in the early morning hours and completes the evacuation. Skeleton forces remain in Berbera throughout the day, with the Italians advancing hesitantly, but it basically is an open city. Local Somali troops choose to stay and retain their weapons, but they are not defending the city.

The Italians do not press their attacks to disrupt the evacuation, even though they easily could. Perhaps this is because of typical Italian military timidity. There is lingering suspicion, though, that the Italians hold back because of peace talks being conducted in the Vatican between Italy and Great Britain which Italy does not want to hinder. This is a highly controversial topic. In any event, such talks (if they occur) ultimately lead nowhere, so there is nothing to point to as firm evidence. However, if one takes the absolute longest view, the Italian forbearance at Berbera may make things easier for them when it truly is time to get out of the war.

Three Australian sailors from HMAS Hobart, which remains in the harbor, are captured at one of the previous blocking positions outside of Berbera around this date and become the first Australian POWs of World War II.

Blenheim bombers of RAF No. 11 Squadron based in Aden bomb the road near Laferug, losing a bomber to little purpose. RAF No. 223 based on Perim Island at the same time also raids Addis Ababa in Abyssinia, destroying some hangars, the Duke of Aosta's personal airplane, an SM.79 bomber, an SM.75 bomber, and three Ca.133 planes in addition to damaging several other planes.

The campaign is a decided British defeat, and Prime Minister Churchill (who has strong views about the Italian military) is furious at everyone involved. As a media event, it is overwhelmed by the climax of the Battle of Britain and thus receives scant attention in the Allied media. However, British prestige in the Middle East and throughout the Arab World, first earned by Lawrence of Arabia during World War I, is shattered.

For Italy, today may be the highpoint of their military involvement in World War II, an unalloyed victory with no downside and insignificant losses. Once they occupy Berbera, they quickly begin converting it into a submarine base.

German/Finnish Relations: Finland remains solidly neutral, but German negotiators propose a trade of German military equipment for Norwegian raw materials such as nickel, along with transit of German troops through the country (which could only be for one obvious purpose...). The Finns, still smarting from the Winter War and all of the territory lost to the Soviet Union, give the proposal serious consideration.

US Military: The keel is laid down on battleship USS Columbia in Camden, New Jersey.

American Homefront: The German-American Bund and the KKK hold an anti-war rally in Camp Nordland, New Jersey, which attracts the attention of protesters.

The founder of the Chrysler Corporation, Walter Chrysler, passes away.

August 1940

August 1, 1940: Two RN Subs Lost

August 2, 1940: Operation Hurry

August 3, 1940: Italians Attack British Somaliland

August 4, 1940: Dueling Legends in the US

August 5, 1940: First Plan for Barbarossa

August 6, 1940: Wipe Out The RAF

August 7, 1940: Burning Oil Plants

August 8, 1940: True Start of Battle of Britain

August 9, 1940: Aufbau Ost

August 10, 1940: Romania Clamps Down On Jews

August 11, 1940: Huge Aerial Losses

August 12, 1940: Attacks on Radar

August 13, 1940: Adler Tag

August 14, 1940: Sir Henry's Mission

August 15, 1940: Luftwaffe's Black Thursday

August 16, 1940: Wolfpack Time

August 17, 1940: Blockade of Britain

August 18, 1940: The Hardest Day

August 19, 1940: Enter The Zero

August 20, 1940: So Much Owed By So Many

August 21, 1940: Anglo Saxon Incident

August 22, 1940: Hellfire Corner

August 23, 1940: Seaplanes Attack

August 24, 1940: Slippery Slope

August 25, 1940: RAF Bombs Berlin

August 26, 1940: Troops Moved for Barbarossa

August 27, 1940: Air Base in Iceland

August 28, 1940: Call Me Meyer

August 29, 1940: Schepke's Big Day

August 30, 1940: RAF's Bad Day

August 31, 1940: Texel Disaster

2020

The Luftwaffe damages British dredge ship Lyster at Liverpool.

Sgt. Bruce Hancock, an RAF pilot, uses his unarmed training plane to ram a Luftwaffe bomber and perishes.

The day's losses are usually touted as 60-75 losses for the Luftwaffe and 30-40 for the RAF. This, however, does not count numerous aircraft (one estimate is 29, including half a dozen fighters) destroyed on RAF airfields, so things are not quite as bad for the Luftwaffe as it might appear based on the aerial combat losses. One can with confidence say that air losses for the day were heavy for both sides and favored the RAF by roughly 2-1, while planes actually destroyed were about even.

However, the numbers also understate the problems caused for the Luftwaffe. The numbers do not come close to reflecting the chaos and the damage suffered. GruppenKommandeur Hptm. Herbert Meisel of I,/StG 77 is killed, Lt. Walter Blume of 7./JG 26 (14 victories) becomes a POW, Oblt. Helmut Teidmann of 2./JG 3 (7 victories) becomes a POW, Staffelkapitän of 5./JG 51 Hptm. Horst Tietzen is killed - the list of very talented and successful pilots lost is long. When that many top pilots are lost, something is going seriously wrong. Fortunately for Adolf Galland, he is at Carinhall receiving a decoration and misses the "fun," but the losses are absolutely crippling for several formations.

The RAF also loses a dozen pilots, and that is not trivial. Most of their men, however, can parachute to safety and be back with their Squadrons by suppertime. The Germans shot down over England are gone for good, and there are scads of them. It is fair to say that neither side really knows how the other is holding up, so the day puts everyone on edge.

The RAF also makes some attacks of its own. RAF Coastal Command attacks Boulogne, and Bomber Command raids the Italian aircraft works at Milan and Turin again. Other attacks are made against Luftwaffe airfields at Freiburg and Habsheim, and industrial targets at Waldshut and Bad Rheinfelden are bombed.

Due to heavy losses, JG 52 is pulled from the Channel and transferred back to Jever to fly defensive missions against RAF Bomber Command. In addition, Ju 87 Stukas finally are withdrawn from attacks inland.

|

| RAF Kenley under attack. The photo is taken from a Luftwaffe bomber. 18 August 1940. |

There is scapegoating everywhere in the German high command. Hermann Goering blames "local commanders," Admiral Raeder blames the Luftwaffe, the Army blames the Kriegsmarine, and Hitler apparently doesn't even really want to invade anyway. One thing is for certain, things have to improve fast or the entire military strategy against Great Britain is bankrupt.

|

| German pilots are given their objectives before taking to the skies in their Stukas, 18 August 1940. Notice how solemn the pilots look. (Credit: Corbis). |

Armed merchant cruiser Circassia eludes an attack by an unknown U-boat, then counterattacks without success (but claims it sank the U-boat). Nobody has been able to identify the U-boat.

Cruiser HMS Delhi stops Spanish freighter Ciudad de Seville and Portuguese freighter Joao Belo. It sends the former to Freetown and interns six Germans on the latter.

Convoys OA 201 and MT 144 depart from Methil, Convoy FN 256 departs from Southend, Convoy FS 256 departs the Tyne, Convoy OB 200 departs from Liverpool, Convoy SL 44 departs from Freetown, BS 3 departs from Suez.

Battle of the Mediterranean: At Malta, there are no raids. Three Blenheim bombers fly in for operations.

|

| A Spitfire at Biggin Hill on or about 18 August 1940. |

The Italians do not press their attacks to disrupt the evacuation, even though they easily could. Perhaps this is because of typical Italian military timidity. There is lingering suspicion, though, that the Italians hold back because of peace talks being conducted in the Vatican between Italy and Great Britain which Italy does not want to hinder. This is a highly controversial topic. In any event, such talks (if they occur) ultimately lead nowhere, so there is nothing to point to as firm evidence. However, if one takes the absolute longest view, the Italian forbearance at Berbera may make things easier for them when it truly is time to get out of the war.

Three Australian sailors from HMAS Hobart, which remains in the harbor, are captured at one of the previous blocking positions outside of Berbera around this date and become the first Australian POWs of World War II.

Blenheim bombers of RAF No. 11 Squadron based in Aden bomb the road near Laferug, losing a bomber to little purpose. RAF No. 223 based on Perim Island at the same time also raids Addis Ababa in Abyssinia, destroying some hangars, the Duke of Aosta's personal airplane, an SM.79 bomber, an SM.75 bomber, and three Ca.133 planes in addition to damaging several other planes.

The campaign is a decided British defeat, and Prime Minister Churchill (who has strong views about the Italian military) is furious at everyone involved. As a media event, it is overwhelmed by the climax of the Battle of Britain and thus receives scant attention in the Allied media. However, British prestige in the Middle East and throughout the Arab World, first earned by Lawrence of Arabia during World War I, is shattered.

For Italy, today may be the highpoint of their military involvement in World War II, an unalloyed victory with no downside and insignificant losses. Once they occupy Berbera, they quickly begin converting it into a submarine base.

German/Finnish Relations: Finland remains solidly neutral, but German negotiators propose a trade of German military equipment for Norwegian raw materials such as nickel, along with transit of German troops through the country (which could only be for one obvious purpose...). The Finns, still smarting from the Winter War and all of the territory lost to the Soviet Union, give the proposal serious consideration.

US Military: The keel is laid down on battleship USS Columbia in Camden, New Jersey.

American Homefront: The German-American Bund and the KKK hold an anti-war rally in Camp Nordland, New Jersey, which attracts the attention of protesters.

The founder of the Chrysler Corporation, Walter Chrysler, passes away.

August 1940

August 1, 1940: Two RN Subs Lost

August 2, 1940: Operation Hurry

August 3, 1940: Italians Attack British Somaliland

August 4, 1940: Dueling Legends in the US

August 5, 1940: First Plan for Barbarossa

August 6, 1940: Wipe Out The RAF

August 7, 1940: Burning Oil Plants

August 8, 1940: True Start of Battle of Britain

August 9, 1940: Aufbau Ost

August 10, 1940: Romania Clamps Down On Jews

August 11, 1940: Huge Aerial Losses

August 12, 1940: Attacks on Radar

August 13, 1940: Adler Tag

August 14, 1940: Sir Henry's Mission

August 15, 1940: Luftwaffe's Black Thursday

August 16, 1940: Wolfpack Time

August 17, 1940: Blockade of Britain

August 18, 1940: The Hardest Day

August 19, 1940: Enter The Zero

August 20, 1940: So Much Owed By So Many

August 21, 1940: Anglo Saxon Incident

August 22, 1940: Hellfire Corner

August 23, 1940: Seaplanes Attack

August 24, 1940: Slippery Slope

August 25, 1940: RAF Bombs Berlin

August 26, 1940: Troops Moved for Barbarossa

August 27, 1940: Air Base in Iceland

August 28, 1940: Call Me Meyer

August 29, 1940: Schepke's Big Day

August 30, 1940: RAF's Bad Day

August 31, 1940: Texel Disaster

2020

No comments:

Post a Comment